Abstract

Gone are the days when the students had only a pile of books to learn English. Technology is increasingly becoming our students’ anytime-anyplace friend on whom they rely for doing their daily activities. As English teachers, we are expected to track the technology footsteps in education for the purpose of bringing real life incidents to our classes while magnetizing the students to learn English. In this context, edutainment empowers teachers to make their classrooms as entertainment hubs for learning English. Digital storytelling and gamification are two tech trends of edutainment. In this article, English teachers explore how they can use edutainment in their classes.

Introduction: The concept of edutainment in interactive classes

Prior to discussing the concept of edutainment, I want to ask you read a brief teaching experience from an imaginary English teacher from a local school in one of the provinces of Iran:

Ms. Faramarzi is an English teacher at Omid School. As a creative teacher, she consistently uses fresh teaching techniques in her classes and regularly updates herself by checking out different websites, watching short video clips, and interacting with collegues on different social networks. Ms. Faramarzi strongly believes that a boring English class is a true nightmare for both the teacher and the students. Her students think that Ms. Faramarzi is their best English teacher because she enthusiastically seeks to bring the students’ daily incidents to English classes so that they enjoy every minute of their class.

A few months ago, the outbreak of Coronavirus led to the closing of schools and the teachers began to use “Shad” platform for resuming lessons. Since then, Ms. Faramarzi has been exploring novel alternatives for making her online classes less teacher-fronted and more engaging for the students to do motivating virtual tasks. It took her days to browse different websites and attend some webinars to find out what techniques the international teachers may use to make their online classes entertaining for the students. A few days ago, as she was surfing the Internet, she came across the word “edutainment”. What is “edutainment”? The following word cloud may help you find the answer.

Edutainment is the practice of entertainment-based education (Sala, 2021) that relies on classroom materials, tasks, and activities to make the teaching-learning process enjoyable and engaging (Pojani & Rocco, 2020). It attempts to promote learners’ motivation, personalize their learning experiences, and engage them in doing creative individual-collaborative problem-solving and critical thinking activities. According to Buckingham and Scanlon (2005), edutainment heavily relies on visual sources, narratives, and game components. It can be either interactive (i.e., having learners actively participate in tasks) or non-interactive (i.e., involving learners as spectators to explore movies, shows, podcasts, or websites) (see Walldén & Soronen, 2004). Technology assists teachers in gradually becoming edutrainers by providing user-friendly digital contents and virtual platforms (Shadiev et al., 2018). In her inquiry, our teacher (i.e., Ms. Faramarzi) similarly found digital storytelling and gamification as two useful entertainment resources practical in her online classes. In what follows, the application of digital storytelling (DST) and gamification for language instruction and practice will be explored.

The potential of digital storytelling for language classrooms

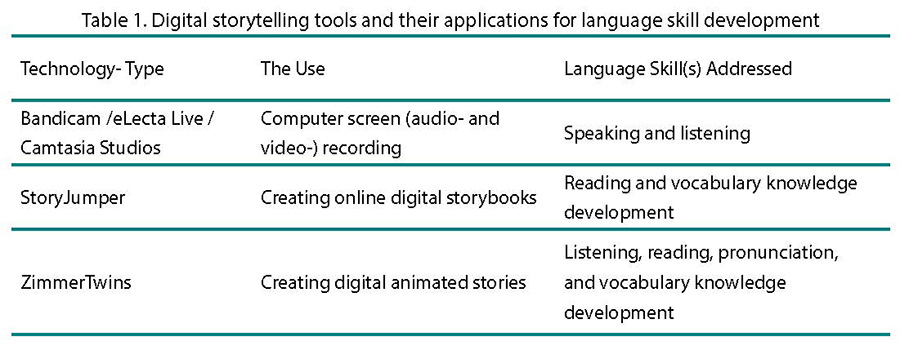

Digital storytelling which can function as a self-standing pedagogy (Wu & Chen, 2020) refers to the application of technology to construct meaning by telling stories (Lambert, 2013). The students as digital natives are digital storytellers (Nami, 2020). In this context, storytelling is “the presentation of personal narratives, involving students’ use of language for expressing meanings in oral, written, and/or visual forms” (Yang, Chen, & Hung, 2020, p. 4). Teachers could either rely on multimedia technological tools-such as screen-recording technologies and online digital content generators; for example, StoryJumper, Bandicam, and ZimmerTwins-to produce digital stories themselves for their classrooms or count on students’ co-creative and interactive digital stories (Schmoelz, 2018). Digital storytelling aims to promote deep learning by means of story plotting and activating students’ learning process through technology-enhanced tools (Tanrıkulu, 2020). Digital stories promote students’ autonomy, motivation, and self-confidence (Hava, 2019). To produce digital stories, students need to go through brainstorming, doing research, defining storyboards, writing stories, gathering or creating multimodal sources, sharing and reflecting on stories, and receiving feedback (Morra, 2014). Producing digital stories is a complicated process which requires teachers’ continuous guidance and scaffolding (Godwin-Jones, 2018):

While reading recent papers published on digital storytelling, Ms. Faramarzi was astonished by the potentials of digital stories for involving her students in multimedia project-based learning. She started to think of supporting her students to make short video clips in which they narrate real-life stories and take real photos to make their digital stories more lively and fascinating. By doing so, they could improve their speaking skills. She even thought about involving the students in rewriting Iranian stories to further develop their writing skills. Ms. Faramarzi even found out that she could run a competition, ask the students to create team-based digital stories, and share these stories with parents, friends, and relatives. Which team is going to win the competition?

The following table lists a number of technology types that can be used for digital storytelling by the teacher and/or learner to enhance different language skills in the learners.

Gamification and language instruction/practice

Similar to digital storytelling, gamification which refers to using game-based features in non-game contexts to make learning motivating and enjoyable (Deterding et al., 2011; Landers et al., 2018) is gaining popularity in education (Sailer & Homner, 2020). In gamified learning, teachers use game elements to engage language learners with the content and guide them to achieve learning goals (Dehghanzadeh et al., 2019). Gamification is not designing a game to teach a lesson, but it is applying game-based thinking to decide how to teach the lesson and continuously develop it on the basis of the feedback provided by learners as players (Folmar, 2015).

Gamified activities satisfy users’ interests by creating addictive compelling experiences for the purpose of motivating them to take actions (Denton, 2019). Accordingly, Charsky (2010) specified the salient features of game elements which include:

– goals of the game which are compatible with learning objectives,

– competition against oneself or another player, rules (real-life limitations),

– choice such as expressive choice (i.e., avatar creation to get motivated), strategic choice (i.e., level of difficulty affecting game outcome), tactical choice (i.e., game played with different playing routes),

– challenges (i.e., learning objective integrated into the game),

– fantasy (i.e., knowledge-developing fantasy),

– fidelity (i.e., real-life replication and immersive experience), and

– context or the authentic story plot.

In gamification-based instruction, teachers define the learning goal by considering game mechanics that set the game rules and environments (such as levels, badges, leaderboards, and points) and game dynamics to shape players’ interactions with game elements (achievement and competition), trigger their emotions, and represent how players evolve over time (Bunchball, 2010). In gamification, teachers need to prioritize players’ expectations rather than adopting one-size-fit-all approach (Ofosu-Ampong, 2020). In other words, the current research strand in gamification is tailoring gamified learning environments to the needs, tastes, and interests of learners as players (Klock et al., 2020):

As Ms. Faramarzi was using the search engines to learn more about gamification, she wondered if gamification is the same as game-based learning. After reading a few articles, she came to realize that while gamification is using game-based elements in non-game contexts, game-based learning is using game to teach content.

Conclusion

In both face-to-face and online classes, English language teachers need to concentrate on edutainment-oriented and task-based activities to motivate students, evoke their emotions, engage them in deep meaningful learning, and turn them into active agents of their learning process. For designing edutainment-based tasks for different classes, the teachers are strongly recommended to take into account the learning goals as well as learners’ language needs and interests. On their path to professional development, English teachers in small fertile communities of practice could share the digital tools they use for enlivening their classes and making the learning process compelling. Furthermore, by sharing their real-life experiences (promises and challenges), they could more properly adapt edutainment sources to their course requirements. By engaging the students in producing edutainment-oriented tasks and activities, students are expected to take more responsibility of their learning and merge the formal education context with their informal daily lives. Through the application of interactive contents, tasks, and quizzes, teachers are expected to effectively scaffold the learning process in online classes.

References

Bunchball, I. (2010). Gamification 101: An introduction to the use of game dynamics to influence behavior. White Paper, 9.

Buckingham, D. & Scanlon, M. (2004). Selling learning: Towards a political economy of edutainment media. Media, Culture and Society, 27(1), 41–58.

Charsky, D. (2010). From edutainment to serious games: A change in the use of game characteristics. Games and Culture, 5(2), 177–198.

Dehghanzadeh, H., Fardanesh, H., Hatami, J., Talaee, E., & Noroozi, O. (2019). Using gamification to support learning English as a second language: A systematic review. Computer Assisted Language Learning,1–24.

Denton, M. (2020). Game mechanics and game dynamics: Gamification 101. Retrieved September 4 from https://www.gamify.com/gamification-blog/gamification-101-game-mechanics-game-dynamics

Deterding, S., Sicart, M., Nacke, L., O’Hara, K., & Dixon, D. (2011). Gamification: Using game-design elements in non-gaming contexts. In Proceedings of the 2011 Annual Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 2425–2428). Vancouver, BC, Canada: ACM.

Godwin-Jones, R. (2018). Emerging technologies. The TESOL Encyclopedia of English Language Teaching, 1–6.

Hava, K. (2019). Exploring the role of digital storytelling in student motivation and satisfaction in EFL. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 1–21.

Folmar,D. (2015). Game it Up! Using gamification to incentivize your library (Vol. 7). Rowman and Littlefield.

Klock, A. C. T., Gasparini, I., Pimenta, M. S., & Hamari, J. (2020). Tailored gamification: A review of literature. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 144, 1–22.

Lambert, J. (2013). Digital storytelling: Capturing lives, creating community. New York: Routledge.

Landers, R. N., Auer, E. M., Collmus, A. B., & Armstrong, M. B. (2018). Gamification science, its history and future: Definitions and a research agenda. Simulation & Gaming, 49(3), 315–337.

Morra, S. (2020). 8 steps to great digital storytelling. Retrieved September 5 from https://digitalstorytelling.coe.uh.edu/page.cfm?id=23&cid=23.

Nami, F. (2020). Selecting 21st-century digital storytelling tools for language learning/teaching: A practical checklist. In F. Nami (Ed.), Digital storytelling in second and foreign language teaching (pp.65–77). New York: Peter Lang.

Ofosu-Ampong, K. (2020). The shift to gamification in education: A review on dominant issues. Journal of Educational Technology Systems, 49(1), 113–137.

Pojani, D. & Rocco, R. (2020). Edutainment: Role-playing versus serious gaming in planning education. Journal of Planning Education and Research, doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0739456X20902251

Sala, N. (2020). Virtual reality, augmented reality, and mixed reality in education: A brief overview. In D. H. Choi, A. Daley-Hebert, & J. Simmons (Eds.), Current and prospective applications of virtual reality in higher education (pp. 48–73). Hershey: IGI-Global.

Schmoelz, A. (2018). Enabling co-creativity through digital storytelling in education. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 28, 1–13.

Shadiev, R., Hwang, W. Y., & Huang, Y. M. (2018). Review of research on mobile language learning in authentic environments. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 30(3–4), 284–303.

Tanrıkulu, F. (2020). Students’ perceptions about the effects of collaborative digital storytelling on writing skills. Computer Assisted Language Learning, doi: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/09588221.2020.1774611

Walldén, S., & Soronen (2004). Edutainment: From television and computers to digital television. University of Tampere: Hypermedia Laboratory.

Wu, J. & Chen, D. T. V. (2020). A systematic review of educational digital storytelling. Computers & Education, 147, doi:https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0360131519303367

Yang, Y. T. C., Chen, Y. C., & Hung, H. T. (2020). Digital storytelling as an interdisciplinary project to improve students’ English speaking and creative thinking. Computer Assisted Language Learning, doi: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/09588221.2020.1750431